One of the biggest myths about Braille is that it’s hard to read or that it’s somehow another language. Neither is true. Braille is just simple, straightforward code. In a cover story this month for Mass Appeal magazine, hip-hop superstar Kendrick Lamar admitted that he was now using Braille, a somewhat curious announcement that piqued our interest here at the LightHouse. Turns out he had stashed a Braille message in the liner notes of his new, Billboard-topping album, To Pimp A Butterfly [listen on Spotify]. “Nobody has caught [it] yet,” he told Mass Appeal, blowing his own cover and explaining that the message, when decoded, would reveal the album’s full title.

But there were some problems. Kendrick hadn’t really created very useful Braille. For starters, there were no bumps. The dots were printed, not embossed, ironically obscuring their whole raison d’être. This wasn’t lost on Lamar, in fact maybe it was intentional: “You can’t [sic] actually feel the bump lines. But if you can see it, which is the irony of it, you can break down the actual full title of the album.” So — it was Braille, yes — but Braille for the sighted. Kendrick is counting on the fact that no one really knows Braille, which is not far off. After all, getting someone with good vision to learn Braille is kind of like getting Winnie the Pooh to start wearing pants — it might happen, but don’t hold your breath. So why should you care about this Braille message, or any Braille at all for that matter?

The answer is literacy. It’s estimated that only about 10% of blind people know Braille, which means 90% of blind people are missing out on millions of the world’s accessible texts. As a newly blind (low-vision) person myself, I don’t read Braille, either. So I couldn’t translate the secret message from Kendrick Lamar myself, either. Luckily we have a whole team of people here to do just that. The folks in our access to information services (AIS) department specialize in this exact stuff — translating and elucidating information — not only here at LightHouse, but for the public. They Braille business cards, restaurant menus, maps, and all other kinds of tactile documents. All I had to do was walk across the hall and ask “Have you guys ever heard of Kendrick Lamar?”

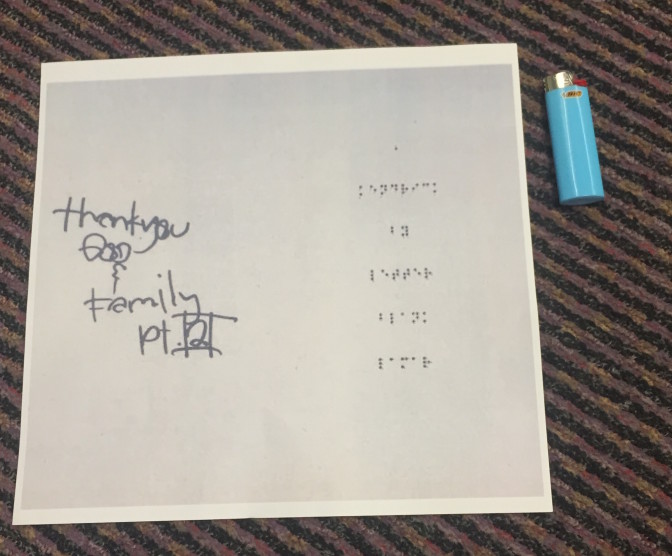

Within minutes, I had a big piece of paper — much bigger than a CD booklet — right in front of me, fully Brailled, courtesy of AIS. The reason they had to blow it up was because the CD-booklet-sized Braille code was actually way too small for a real blind person to read, even if it was raised on the page. This is directly related to the size of human fingertips. In order to differentiate between dots, you need Braille to be a certain size. This is also why converting from small print to to Braille often takes more paper. (If you want to see how many pages a document would take up as Braille, resize the font to 29 pt). Because the original Braille on To Pimp a Butterfly was done in ink, now not only was the Braille message tactile but it was also visual. This is somewhat rare — to have Braille with ink on top of it, that a sighted person can look at and, if not read, at least organize in their mind.

If you’re sighted, look at the photo above; Kind of takes some of the mystery out of what all those blind people are running their fingers across, doesn’t it? If you look at the photo above, you’ll see one simple dot on the first line — that’s the letter “a.” And for those who are interested in Braille learning that’s similarly visual and tactile, we actually offer books like this in our store, along with some other goodies. I still wanted to know exactly what Kendrick’s message meant, though, and I wanted to hear it from an expert.

I brought the Kendrick-Braille to Frank Welte, one of our Braille experts, who coincidentally was munching on one of our dark chocolate, Braille-studded candy bars. His dog Jeep came and said hi first, then I handed Frank the sheet to tell me what it said. He came at it with his left hand — perhaps counterintuitively — peoples fingers are, for some reason, often more sensitive on the left. It only took him a split second before he started translating:

”A Kendrick By Letter Blank Lamar.”

What the hell does that mean? It didn’t make sense. The Braille is actually formatted quite well — the cell spacing was just right, which is something that beginning Braillers don’t often consider. And yet, the words were completely mixed up. Upon further Googling, I found that other Braille experts reached the same conclusion when consulted about the album art. The Braille was actually pretty good, but the sentence was incoherent. Complex magazine figured it must be a mistake. But our expert disagrees.

“People could take a Braille alphabet card and figure it out. But it’s still weird that they didn’t get it in order. There’s no obvious reason why it wouldn’t be in order… They might have intentionally scrambled it just for the fun of it.”

The Braille was in its simplest form, sure — lower case and uncontracted — but there was no reason the words should be shuffled around, unless through human error or intention. We can only conclude that Kendrick wanted to obscure the meaning even further — or just thought that the dots looked cool that way and that no real blind people would actually bother decoding it.

But decode it we did, and diehard fans of the Compton rapper already know where this is going: the words, rearranged, are meant to say “A Blank Letter By Kendrick Lamar.” That’s the real, extended title to To Pimp A Butterfly. We know this because Lamar’s last album, Good Kid, m.A.A.d. City, had a similar subtitle: “A Short Film By Kendrick Lamar.” So there you go. To be honest, it kind of seemed too easy. And our experts agree:

“A lot of people think learning Braille must be terrible, like learning a whole foreign language,” Frank told me later on,”but it’s really much easier than that. The best analogy I can think of is like when you’re a kid, and you learn your printed letters, then you’re introduced to handwriting. It’s the same language, just different-shaped characters. That’s what learning Braille is like, it’s like learning cursive. It’s actually even easier than cursive, because everyone’s handwriting is different, but with Braille, every letter is the same.”

There’s a lot more to say about Braille, but we’ll save that for another day. Most importantly, next time you want Braille done right, whether you’re a famous rapper or not, do yourself a favor and email an expert — hint hint (that’s us).

Email Will Butler at communications@old.lighthouse-sf.org. (Twitter).